Economic and Social Development

Economic and social Development

Syllabus -

Meaning of Economic and Social Development. Human Development

Index (HDI) and Human Poverty Index (HPI).

Characteristics of Indian Economy : Before and After Independence.

Census of India : Economic and Social features.

Population growth and economic development. Issues related to Role of

women in Economic and Social Development in India.

Impact of globalization on Indian society : Poverty and Development.

Poverty-line and Programmes for eradication of Poverty in India.

Schemes for Rural and Social Development - Welfare and Developmental

Programmes including Self Help Groups (SHGs), MNREGA and

community power structure.

Sustainable development and Inclusive growth.

National Income - Measurement and composition.

Regional imbalances and income inequalities in India : Steps taken by the

Government to reduce it.

Meaning of Economic and Social Development (HDI)

Human Development Index (HDI)

Human Poverty Index(HPI); it is replaced by Multidimensional Poverty in 2010

Multidimensional Poverty Index(MPI)

Characteristics of Indian Economy : Before and After Independence

Census of India : Economic and Social features

Characteristics of Indian Economy : Before and After Independence

The economic history of India shows a number of distinct phases over the period it fell under the colonial control to the modern times when it embarked on economic reforms. Before the formal onset of the British colonial rule in India after the battle of Plassey in 1757, India was among the richest countries of the world. According to some estimates during the Mughal period India was the second largest economy having a share of almost 25% of the world economy. Two centuries of the exploitative British colonial rule led to India's wealth being drained away and the process of 'deindustrialisation' taking a heavy toll on the people of India. The great nationalist leader Dadabhai Naoroji was the first person to systematically highlight this aspect of the colonial exploitation. His analysis laid the theoretical foundation for the freedom struggle culminating in India's independence in 1947.

At the time of independence, India inherited a stagnant economy. Between 1900-1950, the

real GDP growth rate of India was almost zero. The independent India embarked on a process of economic reconstruction and growth by adopting the model of planning. The beginning was made with the Mahalnobis-Feldman model which aimed to build the capital goods industry to lay the foundation for self-reliant growth in India.

However, beginning the 1980s winds of change had started blowing across the world in the form of greater international economic integration in the process of globalisation. India realised that its growth rate, sarcastically dubbed the 'Hindu growth rate' of close to 3% annually, was far too low to sustain the expanding aspiration of its people. The distortion in the planned economic process was glaringly reflected in the 'license-permit raj' that empowered the rent seeking class of bureaucrat-contractor-politician to extract surplus from the system. This was the period when economic reforms were initiated, prompted in no small measure by the expanding sphere of finance capital in the world economy.

The process of economic reforms picked up momentum by the early 1990s as India had to undergo structural adjustment in order to avoid defaulting on its international obligations towards debt repayment. The reforms moved apace to include opening up of the economy, decontrol and significant changes in the financial and banking sectors. The

transition from the public sector attaining the 'commanding heights of economy' to the 'market driven open economy' has been a complex and multi-layered process. The transition has indeed resulted in an accelerated GDP growth rate of above

5% for the period 1991-92 to 2003-04 and above 6% for the period 2003-04 to 2011-12. Fall in the poverty ratio, improvement in the FDI and better forex reserves have also been noticeable achievements of this period.

However, this period has also been marked by an increase in the level of inequality in the country. According to a study 'in both the early 1990s and the early 2000s the wealthiest 10% of wealth-holders held at least 50% of total assets, while the least wealthy 10% held at most 0.4% of total assets'. In case of land, it is more unequally distributed than wealth as a whole. The ownership of financial assets is even more concentrated, as 'almost all financial

wealth is held by well below 1% of the population'. It needs to be highlighted that inequality in resource endowment also culminates into inequalities of opportunity which defeats the purpose of inclusive development that India has adopted as a stated objective of its economic policy. There has also been a serious concern about employment generation in the period of economic reforms. The robust growth rate has not really been accompanied with improvement in the employment generation. Similarly, share of manufacturing sector in the GDP has also been quite low at 16%, putting a structural constraint on the future prospect of growth with employment.

Indeed, the rights based model of inclusive development could be successful only when we are able to bring in larger and larger number of people in the 'circuit of capital' for their productive integration in the process of creation of national wealth. After all, the famous economist Joan Robinson has rightly remarked that 'what is worse than being “exploited” is

not to be exploited at all!'

Economic Growth In India – Performance and Prospects

The most comprehensive

indicator of economic

growth in an economy

is the average annual

growth in real Gross

Domestic Product(GDP) that is originating within the

geographical boundary and measured

at constant base period prices. It would,

therefore, reflect average incremental

availability of goods and services

produced domestically in the economy

over time. When the growth of real

GDP is adjusted for the population

growth, it gives the average annual

growth of per capita real GDP and

reflects closely the improvements in

standard of living enjoyed by people

in the economy on an average over

time. This is particularly valid for

large countries where the cross border

flows of goods and services are limited

in relation to the amount produced

within the geographical boundary.

These three average annual growth

rates in: (i) real GDP, (ii) population

and (iii) per capita GDP (PCI) are

very significant parameters to reflect

the performance and prospects of

economic development in any country

over fairly long time period.

History of economic growth in

India is both interesting and educative.

Comparable time series estimates of

real GDP in India can be stretched

back till the year 1900 for meaningful analysis (Sivasubramonian, 2004; and

Hatekar & Dongre, 2005). There is

considerable research on attempting

periodization of the economic growth

history in India to gain insights about

policy regimes and factors determining

the performance of the economy

over long periods of time (Hatekar

& Dongre, 2005; Balakrishnan &

Parameswaran, 2007; and Dholakia,

2014). Accordingly, there are five

distinct phases so far in the history

of economic growth in India: (i)

1900-1901 to 1950-51; (ii) 1950-51

to 1980-81; (iii) 1980-81 to 1991-92;

(iv) 1991-92 to 2003-04; (v) 2003-04

to 2011-12.

The growth performance during the

first phase when the country was under

the last 50 years of the British rule was

the worst during all the phases so far.

Real GDP grew at around 1 per cent

annually and so did the population.

As a result, the per capita real income

almost stagnated for the first fifty

years of the last century in India.

Since the last fifty years of the British

rule in the country were perhaps the

best period for the Indian economy

under their rule of about 190 years in

terms of development of all physical

and social overhead capital such as

railways, ports, schools, colleges,

hospitals, banks and other institutions,

it can be safely assumed that the

stagnation of real living standards of people observed during 1900-51

was perhaps the phenomenon during

the entire period of 190 years of the

British rule in the country. These

two centuries of stagnation ensured

that one of the richest countries in

the world luring everybody by its

wealth and prosperity turned into one

of the poorest countries by the year

1950-51.

The stagnation of real per capita

income for such a long time also

had other implications. Under such

circumstances, if anyone becomes

better off, it cannot happen without

someone else becoming worse off,

because it becomes a zero sum game

under stagnation. Therefore, in the

society people started looking at

progressing few with suspicion that

they would have been involved in

some wrong doing to become rich

by depriving others or snatching

opportunities from others making them

poorer - a perception that continues

even today! Social and cultural barriers to entrepreneurship became stronger

and economic growth in the nation

further suffered. Moreover, long

stagnation in the living standard of

masses implies that their consumption

pattern would not change significantly,

and because there would be hardly any

innovations or technological progress

in the system, people would continue to

consume the same products throughout

their life with little diversity and

change. Rate of product obsolescence

and depreciation was very small and

the culture of preserving things by

recycling, saving resources and using

outdated technology with low material

costs was widely prevalent.

After achieving independence, it

was a major challenge to break out

from such vicious circles of low level equilibrium. Committing ourselves to

achieving self-sufficiency in general

and the socialistic pattern of society by

adopting both economic and physical

planning through creation of public

sector undertakings and imposing

numerous controls, licenses and

high taxes, during the second phase

(1950-81) we achieved the breakthrough

largely through public sector

interventions. In terms of managerial

decision to buy or make, the national

commitment to self-sufficiency

implied complete focus on import

substitution without consideration to

cost of production. It was consistent

with the export pessimism subscribed

by most of the leaders of those days.

Although our share in world exports

started falling significantly, the real

growth of GDP increased to about 3.5

per cent annually over the 30 years

period, 1950-81. Because of a sharp

fall in the death rate due to improved

provisioning of primary healthcare

infrastructure in the rural areas, the

growth of population also increased

substantially to about 2.2 per cent

annually and the per capita income

registered annual growth of meagre

1.2 per cent. It marked an increase

of about 2.5 percentage points in the

annual growth of real GDP, but only

about 1.2 percentage points in per capita real GDP.

The need for reforms in economic

policies was duly recognized in India

in the early 1980s, not substantially

lagging behind China. Several

economic reform measures got initiated

during the 1980s with exchange rates

adjusting continually for differences

in the inflation rates, change in

the approach of monetary policy

to monetary targeting, instituting

new institutions in financial sector,

announcement of long-term fiscal

policy, reducing quota requirements

in selected commodities, focusing on

telecom & information & technology

sector, etc. The economic growth

during the third phase( 1980-81 to 1991-92) further picked

up from 3.5 per cent to 5.1 per cent

annually and the population growth fell

to about 2 per cent. Per capita real GDP,

therefore, started growing at more than

3 per cent annually during the 1980s.

The fourth phase(1991-92 to 2003-04) saw accelerated

pace of implementation of some

systematic economic policy reforms

in various segments of the economy

such as fiscal policy, autonomy of

the Reserve Bank of India (RBI),

commercial policy, capital markets,

aviation sector, banking and insurance

sector, etc. Sequencing of the reforms

was meticulously done starting with

privatizing selected sectors by allowing

participation by the private sector into

those activities reserved hitherto for

only the public sector undertakings,

liberalizing economic activities by

abolishing licensing requirements,

gradually reducing protection by

cutting tariff rates to integrate domestic

economy with the international

economy, allowing foreign direct

investments in the economy and

finally allowing domestic players to

go global and become multinational

companies. The growth of real GDP

further increased during this phase to

6 per cent and per capita real GDP to

more than 4 per cent annually.

During the last phase so far

covering the period 2003-04 to 2011-

12, although no major economic reform

took place, the economy was allowed

to consolidate and adjust to the reforms

already made initially for 5-6 years.

However, during the last 4-5 years,

some reforms got reversed effectively

by introduction of new controls,

regulations, approval requirements,

bans, environmental and ecological

balance oriented clearances and so on.

Favourable global factors prior to the

year 2008 coupled with easy monetary

policy and movement towards fiscal

consolidation resulted in high growth.

Annual growth of real GDP increased

further to 8.4 per cent and per capita

real GDP to more than 6.5 per cent.

Interestingly, critical areas of pending

reforms such as labour reforms,

land market reforms, foreign direct

investment, direct & indirect taxation

reforms, expenditure reforms and so

on are yet not satisfactorily addressed.

These represent the opportunities for

future growth of the economy.

Prospects For Indian Economic

Growth

In the recent past, the best economic

performance of the Indian economy

was achieved during the year 2007-08.

It is important to note some relevant

parameter values during the year

because they have been actually

achieved by the nation in not too

distant past and, therefore, can easily be

achieved again. It represents the lower

bounderies on the potential existing

in the economy. In 2010-11, we came

very close to achieving several of those

parameter values, which indicates the

feasibility and practicality of such a

potential existing in the economy at

present.

In 2007-08, the Indian economy

clocked the growth of 9.3 per cent in

real GDP at factor cost, exports growth

of 29 per cent in dollar terms, inflation

rates of 4.7 per cent (Wholesale Prices)

& 6.2 per cent (consumer prices),

foreign exchange reserves of $310

billion equivalent, average exchange

rate of Rs. 40.3 per dollar, current

account deficit of only 1.3 per cent

of GDP, combined fiscal deficit of 4

per cent of GDP, combined revenue

deficit of 0.2 per cent of GDP and

primary surplus of 0.9 per cent of GDP. Thus, the year 2007-08 was

outstanding in all relevant performance

parameters except consumer inflation.

This was made possible primarily

because domestic savings rate and

domestic investment rate reached their

respective peaks at 36.8 per cent and

38.1 per cent of GDP. The Incremental

Capital Output Ratio (ICOR) reflecting

the efficiency of converting capital

formation into growth of output was

around 4.1.

The performance of the economy

slipped on all these parameters sharply

after the year 2007-08. International

developments in terms of financial

& confidence crisis of 2008, increase

in commodity prices including oil

prices, Eurozone sovereign debt

crisis, etc. led almost all developed

economies into severe recession and

most of the developing economies to

a significant slowdown. Both fiscal

and monetary boosts were provided

all over with a significant collaborative

effort to emerge out of such a slump.

Indian economy could fast recover

and emerged out of the slowdown

initially in terms of regaining the

growth momentum, but failed to reign

in the inflation, twin deficits on fiscal

& current account, steep depreciation

of the currency and loss in foreign

exchange reserves. Public sector

savings fell sharply from 5 per cent

of GDP in 2007-08 to 1.3 per cent

in 2011-12. Savings of the private

corporate sector also fell from 9.4 per

cent of GDP in 2007-08 to 7.2 per

cent in 2011-12. As a result, overall

savings rate in the economy fell by 6

percentage points to 30.8 per cent of

GDP in 2011-12 from 36.8 per cent in 2007-08. Investment rate also

fell from 38.1 per cent of GDP in 2007-

08 to 35 per cent in 2011-12 and 32.3 per cent in 2013-14; and the

growth of real GDP came down to 6.2 per cent in 2011-12. ICOR increased to

5.6 indicating substantial deterioration

in the efficiency of capital resources

that can occur only if the investments

remain under or unutilized.

The government’s failure to take

several decisions of critical importance

and urgency to ensure proper utilization

of natural resources and capital

investments in areas of strategic

importance such as infrastructure provision, raw material supplies,

taxation, providing environmental

clearances, giving timely approvals

for projects with huge investments,

etc. resulted in sharply reducing capital

efficiency and consequently increasing

the ICOR in the system. From the

economy’s potential assessment angle,

all these factors are of temporary nature

and can get reversed very fast. If the

central government starts performing

by taking quick decisions and clearing

the pending cases of approvals, it

may not only provide good incentives

for additional investments from the

private corporate sector but also lead

to improvements in utilization rates of

existing projects. All this can result in

reducing the ICOR back to the level

achieved in 2007-08. Similarly, the

central government can reign in the

fiscal discipline soon to ensure a rise

in the public sector saving back to the

level of 2007-08.

Thus, achieving the domestic

savings rate of 36.8 per cent in near

future is very likely. Then, attaining

the investment rate of 38 per cent

is also quite feasible. However, the

future potential of India is far more

attractive, because India is among the

few economies currently in the world

enjoying the demographic dividend.

The proportion of population in the

employable age group of 20 years to

65 years is on the rise in the country

and is likely to continue rising till about

2027-28 as per the UN projections.

Thereafter it may stabilize for a while

and then start falling. To attain the

current level of the ratio, it may take

another 15-20 years because the life

expectancy in the country is also likely

to rise in the meantime, but the further rise would be necessarily slower as we achieve higher levels.

Since the dependency ratio would be falling in the country till

2027-28, domestic savings rate is most likely to rise further to

reach the levels already reached in south-east Asia of 40-42 per

cent of GDP. If the efficiency of capital resources is maintained

with the ICOR staying at 4.1, this in itself would generate an

annual growth rate of 10 per cent of real GDP. This is purely

domestically funded growth potential. We expect that such a

high growth momentum is most likely to attract huge foreign

investment in search of better returns and dynamic markets.

Similarly our companies would reach out to foreign destinations

to expand their markets. If we assume a net inflow of only 2 per

cent points, it would push our annual growth potential upward

to 10.5 per cent over a fairly long period unto 2050.

Population growth rate is likely to slow down considerably

and would be about annual 1 per cent on average. Then the per

capita real GDP is likely to grow at around 9 per cent annually.

This is a mind-boggling scenario where the per capita real

income would be doubling every 8 years. The availability of

goods and services would be increasing at an unprecedented rate

and so would be the consumption of people. With such a high

speed of expansion in the consumption basket, the consumption

pattern would be changing drastically and rapidly. The basket

would be highly diversified and ever changing. Rate of product

obsolescence and depreciation would be very high. Preserving

goods would not be found viable and feasible. Recycling of

products and resources could become a formal business but

affording it within the household could be almost ruled out.

Service sector, entertainment, information, communication,

research and development are the fields most likely to come to

prominence. In short, the first fifty years of the current century

are likely to be quite opposite to the first fifty years of the last

century in India.

In such a dynamic and fast pace of economic growth,

entrepreneurship and diversity of consumption would require

considerable resources devoted to research and development.

This would require qualitatively a much superior human

resource development strategy. For a business enterprise, to

survive and maintain one’s relative position, rapid growth in

labour productivity, technological improvements and emphasis

on exclusive products would be the key. Emphasis and reliance

on the private sector participation is likely to address most of

these concerns as a part of their self-interest.

Is India back to the Hindu Growth Rate?

India’s post economic

reforms growth has been

one of the most cited

examples by economists

in last many years.

A h l u w a l i a ( 1 9 9 5 ) ,

Srinivasan (2002), Stern (2004),

Virmani (2004), Tendulkar and

Bhavani (2007), Panagariya (2008),

Bhagwati and Panagariya (2012.) to

name a few are among some of the

leading contributors in this regard.

India was blamed for its inwardlooking

industrialization from 1950-90.

Growth got a new boost from India’s

macroeconomic reforms when it

moved from inward looking to outward

looking industrialization. This was in

anticipation of the policy makers that

Indian economy would achieve faster

economic growth. But, the growth in

the post reforms period has become

a matter of debate. Economists argue

that India is an open economy where

the Hindu Growth Rate is far from

the reality. To get an external linkage

in this particular paper, the Pearson

correlation coefficient (r) finds the

strength of the linear relationship

between the GDP Growth and trade

deficit in India.

Growth Rate vs. Hindu Growth

Rate

Economic growth is defined as the

steady process by which the productive

capacity of the economy is increased

over time to bring about rising levels of national output and income (Todaro

and Smith, 2003). Samuelson and

Nordhaus (2007) assert that economic

growth represents the expansion of a

country’s potential GDP or national

output. Soon after the independence,

Indian Economy was facing chronic

imbalances as part of colonial rule.

Indian economy was left with weak

industrial base, poor infrastructure and

static economy. India made the first

declaration of industrial policy in theirresolution dated 6th April, 1948 in

which both public and private sectors

had been given importance.

India followed the planning model

that was adopted in socialist countries

including former USSR. In tune with

the socialist central planning model,

India started its planning beginning

from 1951. However, the development

of industries was left in shadow during

first five year plan. The gloomy picture

of industrialization and sub normality

as part of industrial development can

be traced through the facts. According

to the 1st Five Year Plan, on the one

hand, factory establishments in the

country accounted for merely 6.6

per cent in 1948-49 as a proportion

of national income and on the other,

only 1-8 per cent of the working

population were engaged in these

establishments.

A new industrial policy statementwas announced on 30th April, 1956 (The Industrial Policy of year 1956 is known as ECONOMIC CONSTITUTION of the country.). It

was aimed at accelerating the process of industrialization and specifically

developing large scale heavy industries.

The new revised industrial policy

includes Schedule A and Schedule B.

Schedule A included industries which

were the exclusive responsibility of the

state - monopoly of the state. Schedule

B included mixed sector of public and

private undertakings. All the rest of

the industries were left for the private

sector to establish and operate.

The Second Plan(1956-61) was particularly in the development of the public sector. The plan followed the Mahalanobis model, an economic development model developed by the Indian statistician Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis in 1953. Hydroelectric power projects and five steel plants at Bhilai, Durgapur, and Rourkela were established. Coal production was increased. More railway lines were added in the north east.The Tata Institute of Fundamental Research was established as a research institute.

The Third plan(1961-66) was largely devoted

to long run benefits and was in tune

with the objectives of increase in the

national output and income generating

huge employment. The focus was on the

development of capital and producer

goods industries. It also emphasized on

the development of machine-building

industries. However, the growth rate of

industrial output declined, initially at

slow pace and after that, it decelerated

sharply reaching stagnation levels.

This created serious concerns for

nearly three years when the economy

fluctuated. The year 1968-69 showed

a clear sign of recovery. Fourth Five

Year Plan (1969-74), was marked

by a very low growth in industrial

production of 3.9 per cent against the

targeted rate of 8-10 per cent.

Fifth Five Year Plan(1974-79), started in

1974, proposed to achieve growth

with the attainment of self-reliance.

The emphasis was on the industries

of core-sector like- iron & steel, nonferrous

metals, fertilizers, mineral

oil, machinery-building, coal and

others. The economy was faced with

pressures and the industrial growth rate

was low at 2.5 per cent in 1974-75.

It was 5.7 per cent in 1975-76 which

provided some relief for the economy.

Sixth Five Year Plan(1980-85) was started in

1980. Substantial policy changes were

announced during this plan. The Sixth Five-Year Plan marked the beginning of economic liberalisation. Price controls were eliminated and ration shops were closed. This led to an increase in food prices and an increase in the cost of living. This was the end of Nehruvian socialism. Industriallicensing and controls were relaxed

and import policy was more liberalized

than ever before. The result was that

growth was witnessed in industrial

production. Seventh Five Year Plan

was started in 1985.The emphasis

was on development with growth and

increase in productivity. The industrial

growth rate during this plan was 8.5

per cent against the target of 8.4 percent. Thus, it was successful on the

part of industries.

Ahluwalia (1995) pointed out

that the inadequacy of the growth

performance of the Indian economy

led Prof. Raj Krishna to coin the

much quoted phrase 'the Hindu rate

of growth, to specify the disappointing

trend of growth. The Hindu growth rate

has nothing to do with any specific

religion; rather it is a term that was

economic in nature. It was a caustic

remark on the socialist pattern that

was adopted by the government after

the Independence. It was an indication

of low and almost stagnant growth

of Indian economy during 1950s to

1980. The average annual growth rate

of GDP during this period was 3.5

per cent. The growth rate of GDP has

shown in table1:

GDP growth rate from 1950-1979

Decades GDP growth Rate

1950-59 3.3

1960-69 4.4

1970-79 2.9

1950-79 3.5

Virmani (2004), asserts that the

new economic policy introduced

in 1991-92 had changed the Indian

economy and pushed it from the Hindu

rate of growth to a new higher rate of

5 per cent-6 per cent, called as, new

Hindu rate of growth.

Slow-down Growth Linkages

Growth potential of Indian

economy can be gauged in two

ways: quantitative and structural. To

understand the quantitative aspects,

growth rates of different sectors and

overall GDP growth are considered.

But to understand the economy well,

structural aspects have to be considered.

Changes in sectoral distribution of

GDP give the more realistic account

on the part of economic growth of the

country. Agriculture dominated the

sectoral composition of the GDP till

1970. In 1950-51 agriculture and allied

sector’s share in GDP was 55.3 per

cent. Two decades of planning in India,

did not show any significant decline

in the share of agriculture and allied

sector. This was the manifestation of

the fact that industries were indeed in a

bad condition in India. The process of

industrialization was not smooth and

not contributing significantly.

Growth Trends after Reforms

The crisis of 1991 led the Indian

policy makers to think beyond the

policy of import substitution to outward

oriented export promotion model. The

Indian economy was integrated with

the economies of the world. Reforms

were initiated in industrial policy and

foreign investment policy, trade and

exchange rate policy, tax reforms,

public sector policy, financial sector

reforms, reforms in agricultural sector,

labor market reforms and others. The

results of these reforms were seen soon after the reforms. The GDP growth

rate which was merely 1.43 per cent

in 1991-92, increased to 5.36 per

cent in 1992-93.

Agriculture & Allied Sectors

Indian economy was heavily based

on agriculture. Its importance can be

evaluated on two grounds- share in

GDP and in employment. So there

is a need to address the problems of

agriculture. The low production and

productivity poses constraints on

the total output of agriculture. The

inefficiency on the part of agriculture

merits sound policy implications

and investments. A very alarming

characteristic of agricultural sector is

that real investment in agriculture, both

private and public, has been stagnant

(Ahluwalia, 1993). This, with other

structural factors, led to slow growth

in agricultural and allied sector.

Industry

The economic reforms were

more radical as far as industries

were concerned. Changes in the

policy framework gave a big boost

to industries. The major reforms

were the abolition of licenses to a

wide range of industries. Licenses

are required now only for some

industries. Industries have thus grown

significantly during the last two

decades after the reforms. Average

growth rate from 1991-92 to 2010-11

was 5.7 per cent with a peak growth of

12.17 per cent in 2006-07 and lowest of

0.34 per cent in 19991-92.

Service Sector

The service sector in India after

the reforms has dominated the sectoral

composition of GDP. The share of

services in 1991-92 was 43.9 per cent

which rose to 59.29 per cent in 2012-

13.There is a sharp increase in IT,

telecom, banking service, insurance,

entertainment and many more. But,

it’s also true that only few services

are performing well. Today, India is

well known for IT and IT-enabled

services (ITES), communication and

BPO. The growth of service sector

after the reforms shows a relatively smooth trend compared to agriculture

and industries. The growth rate which

was 4.69 per cent in 1991-92, started

increasing and witnessed double-digit

growth in several years.

Performance of Indian Economy

There are different phases of

growth of Indian economy. Before

1980s, there was relative stagnation

in the economy, with average growth

rate of GDP at 3.5 per cent. Partial

reforms were started during 1980s. But

total reforms were initiated only after

1991. The currency crisis of 1990s

compelled the policy makers to initiate

the reforms.

GDP started peaking after reforms.

External Linkages

Domestic sectors have been

discussed till now. To analyze the

economy completely, it is imperative

to understand the external linkages

of growth also, comprising exports

and imports. Trade balance remained

negative since long. There has been

trade deficit in the balance of payments

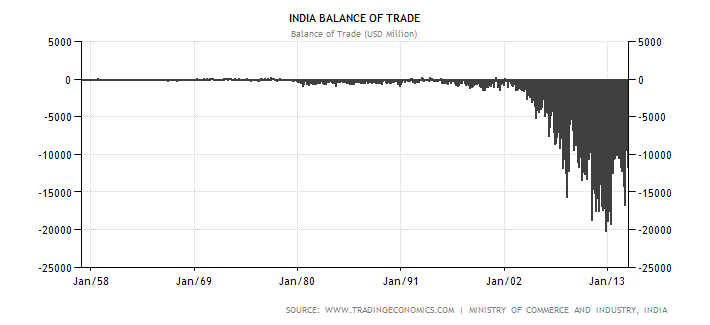

account. Below diagram shows trade balance

and GDP growth rates from 1957 to 2015.

The correlation coefficient between

GDP growth rate and trade deficit

is found to be 0.58. This indicates

that there is a moderate positive

relationship between these two. The

value of correlation coefficient shows

that when GDP increases, India’s

trade deficit also increases (though

moderately), indicating that the exports

are not responding as fast as compared

to imports. These growth rates indicate

that the reforms had certainly brought

more imports which has contributed

in our growth because such range

of growth rate (1991-2010) has not

been achieved by India before trade

liberalization started in 1991.

Recent Growth Trends

The Indian economy is facing

problems that are reflected through

the facts released by the Ministry of

Finance, Department of Economic

Affairs during recent couple of years.

Quarterly data released from 2010-11

to 2012-13 related to the growth rates

of agriculture & allied sector industry

and service sector have been shown

in Table 5.

Agriculture & allied sectors have

been performing poorly. This is the

most fluctuating sector – growth rates

have fluctuated between peak rates

of 11.0 per cent in quarter 3 (Q3) of

2010-11 to mere 1.2 per cent in quarter

2 (Q2) of 2012-13. Average growth rate

during this period was 3.4 per cent.

Industrial sector is also a matter of

concern for the policy makers and the

government. Industries have grown on

an average of 4.4 per cent during Q1 of

2010-11 to Q2 of 2012-13. However,

service sector shows a steady trend

during this period. Average growth

rate in this sector stood at 8.6 per cent.

Overall GDP growth rate during this

period was 6.9 per cent.

Conclusion

Compared to the pre reforms era,

Indian economy had much faster

economic growth in the post reforms

period. But, the recent revised forecasts

released by ADB and others on the

growth of Indian economy provide

a glimpse of slow down of Indian

economy.

Agriculture and allied sector is still

a matter of concern as it is the most

fluctuating sector in the Indian economy.